[Editor’s Note: This piece was inspired by “We Could Be Heroes: Revisionist Gaming & Representation.” It’s recommended that you read it first!]

In March 2013, media critic Anita Sarkeesian launched the video webseries Tropes vs. Women in Video Games where she argues that games are subject to gendered biases. The Legend of Zelda is one of the gaming franchises Sarkeesian critiques in the first episode of Tropes vs. Women, as many of the Zelda titles contain classic examples of a trope that she refers to as “damseling.”

Damseling, in its purest form, is the process by which a woman is rendered inert and thereby positioned as an object that will motivate the player character—a man—to complete his quest. The point of the game is therefore to rescue the damsel in distress, who is subordinate to the hero and is not allowed to rescue herself, generally because she is, as Sarkeesian puts it, “Stranded in a hostile area, trapped, desperately ill, or suffering any number of terrible fates where she needs help to survive.”

In the Zelda series, Princess Zelda is frequently such a damsel, as she is variously kidnapped, imprisoned, placed into an enchanted sleep, crystalized, zombified, and turned to stone. The player’s job, as a young man named Link, is to acquire a weapon powerful enough to defeat the villainous Ganondorf and save Zelda, a narrative that forms the core of the eponymous “Legend of Zelda.”

What do players who are women make of Zelda’s role in this story? Is it necessary to take the plot elements of the series at face value, or are other interpretations possible? How do the games look from Zelda’s perspective?

And what about Ganondorf? What does it mean to be cast as the villain, unable to argue your own side of the story? Are the motivations of “the bad guys” ever so clear cut that we, as players, should feel justified in murdering them? Are there other ways to resolve the conflicts they represent?

Professional illustrator Lorraine Schleter‘s ongoing webcomic A Tale of Two Rulers offers a dramatically different perspective on the recurring story presented by the Zelda series. In A Tale of Two Rulers, an adult Princess Zelda attempts to prevent a war with Ganondorf by suggesting that he marry her. She proposes that, instead of taking her kingdom by force, Ganondorf can occupy the throne legally and peacefully as her husband.

Zelda is well aware of the destruction and bloodshed that Ganondorf’s past incarnations have visited on the kingdom of Hyrule, and she understands that the cycle of violence he represents will not end with his execution.

Although Ganondorf has already marshaled an army composed of the supposed “monster” races that exist on the borders of Hyrule, Zelda approaches him not as the leader of an opposing army but as an individual who hopes to eliminate the need for pointless bloodshed. Because she is a princess without any surviving relatives who are men, Zelda knows that she can further ensure the stability of her nation by solidifying her position through marriage.

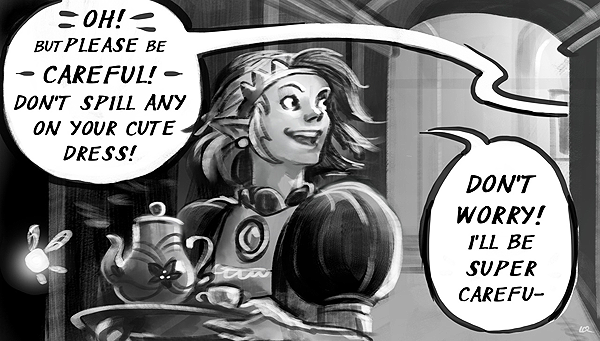

At the beginning of the story, Zelda explains to Ganondorf, “I will satisfy your lust for my lands and my piece of the Triforce. We will rule the kingdom together. I’m not asking for a loving marriage, but rather a respectful partnership.” Although Ganondorf looms over Zelda, seeming to threaten her, she holds her ground and convinces him to act in their mutual best interests. From that point onward, A Tale of Two Rulers mixes intrigue with comedic situations arising from Zelda and Ganondorf’s different cultural backgrounds and the resulting disconnect in their expectations regarding the nature of the relationship they attempt to establish.

A Tale of Two Rulers portrays Zelda and Ganondorf as equally powerful partners who must nevertheless overcome generations of cultural prejudice. Early in the comic, it is revealed that Ganondorf’s homeland in the desert to the west of Hyrule was destroyed by the kingdom’s soldiers, and he is understandably angry that his people, the Gerudo tribe that appears in Ocarina of Time, were stereotyped as thieves and barbarians. Ganondorf does not trust the members of Zelda’s court, who in turn are resentful of his presence in the castle.

Meanwhile, Zelda suffers from her society’s sexist assumptions that a woman is unsuited to wield power and cannot serve as an effective leader. The hostility directed toward Ganondorf as a racial and cultural outsider is a reflection of Zelda’s own unstable position as a woman monarch, and she struggles to exercise the authority that would have come easily to her had she been born as a man.

Zelda is rational and calm, but the repression of her emotions takes a clear toll on her, and she is shown staying up late into the night to catch up on her work. Despite her obvious competence, Zelda has still internalized many of the misogynistic double standards that pervade the culture of Hyrule. Ironically, it is Ganondorf—hailing from the matriarchal culture of the Gerudo—who supports and encourages Zelda.

As the partnership between the princess and her erstwhile enemy develops, the tensions that arise between them serve as a means of revealing the ideologies that underlie the foundational narrative of the Zelda series. In the original games, villains are meant to be vanquished, while damsels are meant to rescued. By positioning Ganondorf as Zelda’s ally, A Tale of Two Rulers encourages the reader to reimagine Zelda outside of the damseled role she so often occupies in the games. Instead, the comic experiments with alternatives to the toxic conceptions of femininity and masculinity by which Zelda and Ganondorf are cast as victim and aggressor.

In her recent article “We Could Be Heroes,” Charlotte Reber argues that when people who don’t see themselves in their favorite games are “failed by canon representation, we try to put ourselves into the games in other ways. We hunt for the cracks, the gaps, the spaces in meaning left intentionally or unintentionally by the creators.”

A Tale of Two Rulers is a gorgeous manifestation of this tendency to seek out and actively create representation when none exists in the source texts. The comic refracts the world of the Zelda games into a reflection of the world as it actually exists, not shying away from controversial themes as it challenges the problematic notions surrounding vulnerability of women implicit in many video game narratives.

While A Tale of Two Rulers focuses on Zelda and Ganondorf, its portrayal of Link is also interesting in the light of Zelda series director Eiji Aonuma’s oft-quoted statement at this year’s E3 that Link will have nothing to do if Zelda becomes a playable character. In the imagined timeline of the comic, Rinku (the pronunciation of Link’s name in Japanese) is a charming and rambunctious girl who has come under Zelda’s care. Although it isn’t clear whether Zelda is Rinku’s biological mother, she loves the girl like a daughter and tries to shelter her from her fate as the reincarnation of a legendary hero.

Rinku still manages to exhibit heroic tendencies, however, and she often finds herself at the center of adventure. Regardless of her gender, young Rinku is easily recognizable as the bearer of the Triforce of Courage who has acted as the protagonist of the Zelda series. Just as so many fans of the games have argued in response to the developers’ insistence that Link must be a man, Rinku’s characterization successfully demonstrates that gender has no bearing on what it means to be a hero.

A Tale of Two Rulers is deeply intertwined with the broader discussions of representation in video games that are currently occurring in lady-centric fandom communities. As these fans pose critical questions concerning their continued marginalization in mainstream gaming cultures, they also produce compelling reconfigurations of sexist narratives and tropes, transforming the games they love into stories that celebrate positive representations of diversity.

A Tale of Two Rulers updates every Monday and can be found on artist Lorraine Schleter’s Tumblr page!

Leave a comment